City plan scrapped

Money began to run out and more and more people were beginning to realize that old buildings also had value. When the threat of demolition was officially removed, Hufvudstaden could once again refurbish its buildings around Biblioteksgatan and Birger Jarlsgatan.

Market rents

In 1972, a political decision was reached that was to be of major significance to Hufvudstaden. The government rent controls that were introduced in 1942 were dropped for all non-residential buildings. Once rents became a matter for negotiation between property owners and tenants, both parties could start to make demands on each other. Hufvudstaden began to focus seriously on its customers and offer premises that justified an increase in rent.

Clear-out

Lars Öberg, who became president of Hufvudstaden in 1976, first came to the Company as head of development in 1970 although he was equally involved in the divestment of what was quite a varied range of holdings that for different reasons had become part of the Company. Involvement in the leisure business was discontinued, construction companies were divested and the wholly-owned film company SF was sold to Dagens Nyheter.

Bygg-Oleba

When Hufvudstaden purchased the construction company Bygg-Oleba in 1979, several well-managed properties were included, such as Orgelpipan 7 on Klarabergsgatan and the historic Räntmästarhuset on the corner of Skeppsbron and Slussplan. Not to mention the Femman Shopping Precinct in the Nordstan Shopping Centre in Gothenburg, which comprised several floors with offices and what was at the time the largest shopping centre in the country.

Investment in Gothenburg

During the 1970s, Hufvudstaden invested in two blocks on Södra Hamngatan in Gothenburg. A new office building was completed on the Härbärget block in 1975 and in 1986 Hufvudstaden’s new hotel was opened on the Slusskvarnen block. The hotel, which was run by Sheraton, failed to generate a profit and did not fit in with the Company’s core operations and was sold in 1999.

Tokyo

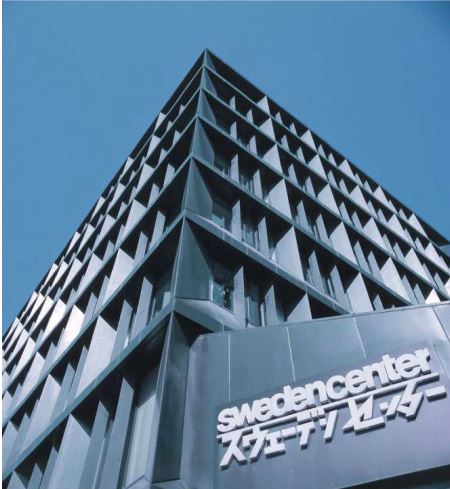

Tokyo

In collaboration with the company Statsföretag and the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences, Hufvudstaden had the opportunity to construct the Sweden Building in Tokyo. The eightstorey building was opened in 1972 and Hufvudstaden soon became the sole owner of the property. The restaurant on the ground floor was run by a restauranteur who had been recommended by King Carl Gustaf after he had visited another establishment in Osaka. The property was sold at the end of the 1990s with a good return.

Trans Match

In order to purchase properties abroad, a permit was generally required from the Swedish Central Bank to transfer money out of Sweden. In 1984, Hufvudstaden was able to acquire foreign properties in a much simpler way – by purchasing the Swedish Match property company Trans Match. The company had holdings in Amsterdam, Lisbon and Oslo as well as an historic palace at Place Vendôme in Paris, which was at one time owned by Ivar Kreuger. Also included in the purchase was a newly constructed office building at Kungsträdgården.

London, Paris and Berlin

Following the abolition of exchange controls in 1987, investing abroad became much simpler. Hufvudstaden identified London and Paris as the most interesting markets and during a temporary downturn in the rental market it acquired a number of centrally located properties. These were then refurbished according to Swedish standards – much to the surprise of local builders.

Öresund steps in

When the market realized that the cross-ownership between Volvo, Skanska and Hufvudstaden’s parent company Custos was in the process of dissolving, the investment company Öresund saw an opportunity. In 1995, Öresund became the majority shareholder in Custos and thus controlled Hufvudstaden, which was split into an international division and a Swedish division. The idea was to sell off the international property holdings. The president, Olov Agri, who had argued for 10 years in favour of a continuation of international investment, stepped down in 1997, shortly after the decision was taken.

Following the fall of the Wall in 1989, Berlin also became an attractive proposition and Hufvudstaden subsequently constructed a building in the city. To meet the cost of this substantial overseas investment and to maintain the share dividend, the Company sold a number of assets – including its residential holdings in Stockholm – to various institutions, one of which was the Nobel Foundation.

Refurbishment of Kungsgatan and Norrmalmstorg

Following the disappearance of the trams in 1967, Kungsgatan had gradually fallen into disrepair and lost its position as one of the most fashionable streets in the city. To help the street recapture its former glory, Hufvudstaden and other major property owners joined forces with the City of Stockholm to invest in an ambitious plan to breathe new life into the street environment.

Pavements, signs, facades, bridges – everything was given a massive facelift. Norrmalmstorg was also modernized in the same spirit at the beginning of the 1990s.

Pavements, signs, facades, bridges – everything was given a massive facelift. Norrmalmstorg was also modernized in the same spirit at the beginning of the 1990s.

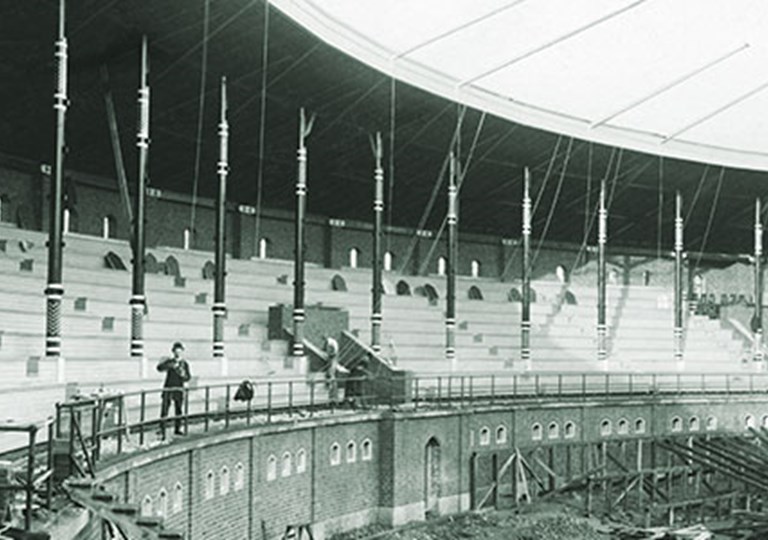

World Trade Centre

Together with SIAB and Lundbergs, Hufvudstaden was assigned the task of building a large terminal across the SJ rail tracks at the Central Station. The World Trade Centre, which was opened in 1990, had 46,000 square metres of floor space, housing offices, shops, a hotel and other activities. In 2000, Hufvudstaden became the sole owner of the property before eventually selling it in 2006.

Property and financial crisis

In autumn 1990, in the same week that Hufvudstaden celebrated its 75th anniversary, the property and finance market was hit by a crisis. The credit economy had begun to veer out of control and finally crashed. The banks were bleeding money, the Swedish Central Bank raised the interest rate to 500 per cent and many property companies went under. And yet Hufvudstaden managed to survive the crisis almost unscathed. The simple reason was that the Company had refused to be dragged into the lending merry-goround and stubbornly insisted on maintaining its considerable financial strength.